On Wednesday, Win Rozario's family, speaking to the press for the first time since New York Attorney General Letitia James released the harrowing body camera footage of his death, described him as a teenager with a firm sense of right and wrong, a kid who loved cooking and playing basketball and picked up litter off the street whenever he noticed it. But Rozario's family did not hold a press conference just to share those memories—they did it to call for the police officers who Tased and shot Win to death in March after responding to a 911 call to be punished.

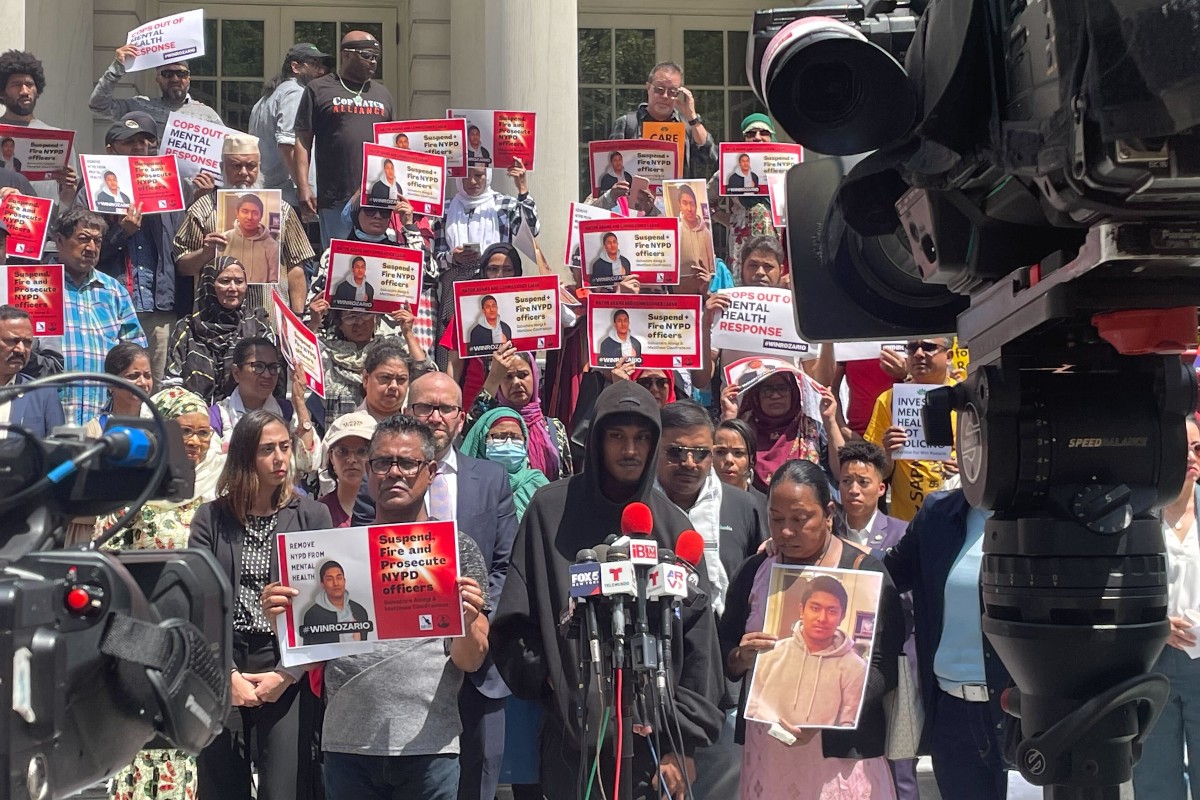

Once the body-worn camera footage from the cops who killed Win, NYPD officers Matthew Cianfrocco and Salvatore Alongi, was released to the public more than a month after his death, it revealed a true nightmare encounter—one that escalated in the span of two minutes to Win lying dead on the floor of his family's kitchen, Tased and shot by cops ostensibly sent there to help him, while his mother and brother screamed and cried. Win's mother, Notan Eva Costa, cried as she spoke at the press conference, organized by the Justice Committee and Desis Rising Up & Moving, too. Speaking in Bangla, she told the crowd through a translator that she missed her son terribly. "You can't imagine the pain I have," she said. "These police were grown men with guns. They didn't have to kill my child. I tried to protect my son. I begged the police not to shoot, but the police still killed him."

Costa's living son, 17-year-old Utsho Rozario, was stone-faced as he spoke, with the hood of a black Fear of God sweatshirt pulled up over his head in spite of the heat and sunshine. "The past 42 days have been hard and painful for me and my family," he said. "I'm angry and disgusted…if anyone who wasn't a cop did what Alongi and Cianfrocco did, they would have already been in jail. But yet, they're still collecting their paycheck from the City like nothing happened." Win's father, Francis Rozario, said through a translator that he believed officers entering the home of a different family—a white, wealthier home—would not have taken the same actions that led to his son's death. Now, he said, his family's relationship with the City is permanently fractured: "If my wife or son [Utsho] gets injured or sick, I don't feel like I can call 911, because I'm afraid of what the police will do when they come."

The family declined to give reporters any information about Win's mental health history. Instead, they talked about what happened after Win died. "After he died, the NYPD treated me and my mom like criminals and the City treated my family like we didn't matter," Utsho said. That day in March, he was wearing shorts, and it was "freezing cold outside," but the officers refused to let him change, or let his mother grab medication or the family cat. He said that he and his mother were held at the police station for hours and questioned. After they left the police station, Utsho said they were barred from their home for the next 48 hours—and when they returned, they found that the NYPD had left Win's blood on the floor of the kitchen for them to clean. "They didn't care to see if me and my mother were OK. They seemed to be more worried about how they would cover this up," Utsho said.

The family's demands were firm: Officers Matthew Cianfrocco and Salvatore Alongi must be immediately suspended, then fired from the NYPD and prosecuted for murder by the New York Attorney General's Office. Utsho also called for accountability from Mayor Eric Adams, who released a statement on Win's killing—that misspelled Win's first name—for the first time on Friday, after the body camera footage was released. "Our deepest condolences to Winn's friends, family and loved ones during this unfathomably difficult time," the statement read, before delving into the mayor's time advocating for police reform as a transit police officer and member of 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care. "As your mayor, I am committed to continuing this lifelong mission and ensuring that Winn's death is not in vain," he continued, and added that he would cooperate with the Attorney General's investigation into Win's death.

Yet Adams, as some speakers at the press conference noted, repeatedly cut funding for the pilot program B-HEARD, an initiative that was supposed to put social workers and emergency medical technicians on the other end of 911 calls related to mental health crises. (As the CITY noted, the precinct where Win was killed was not participating in the pilot.)

"My brother is dead and the mayor is acting like it's something he doesn't have to talk about," Utsho said. "Not only does he need to comment, he needs to explain why he let the NYPD try to cover this up by refusing to release Alongi and Cianfrocco's names. He needs to suspend them without pay and then fire them."

Members of DRUM, the Justice Committee, and other activist groups from around the city stood behind the Rozario family on the steps of City Hall, and City Councilmembers Sandy Nurse, Alexa Avilés, and Shanana Hanif—New York's first councilmember of Bangladeshi descent—all echoed the family's calls for Alongi and Cianfrocco to be suspended, fired, and prosecuted for their role in Win's death.

But hope was not among the feelings that radiated from the Rozario family and the other speakers present. Again and again, they evoked the names of other people in the midst of a mental health crisis who were killed by the NYPD —Kawaski Trawick, Deborah Danner, and Mohamad Bah. Bah's mother, Hawa Bah, addressed the crowd of reporters. "When I met this family last time, Win's mom could not even stand by herself," Bah said. "I said, 'I know how you feel.'"

Loyda Colon, the executive director of the Justice Committee, told Hell Gate that Win's family is all too aware that their fight could be years long and ultimately fruitless. "A lot of these families have to wait half a decade, if not more, for anything related to discipline, for any answers as to whether or not these officers [who killed their loved one] are going to be fired. And what we're saying is that Mayor Adams can't let that happen in this case," Colon said. "This is what they have to resort to. They have to come outside of the mayor's office, the mayor's home, go to the attorney general, the CCRB, the NYPD. The only thing they can do is continue to fight: protest, send letters, emails, press conferences, rallies, go on social media and try to gather more support—and it is disgusting that families have to go through that."