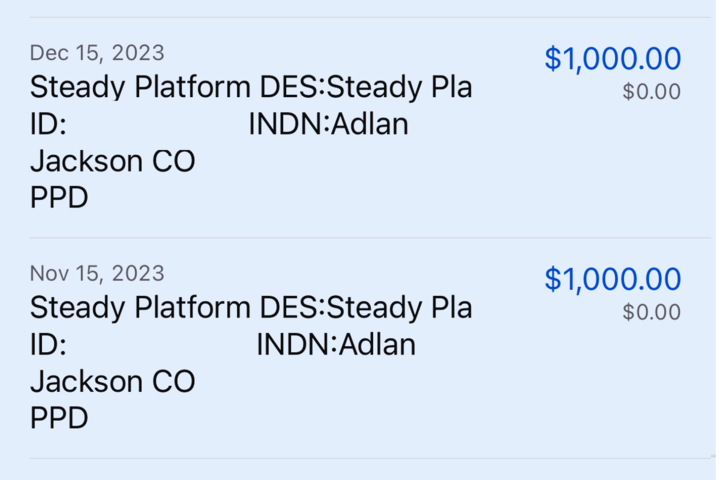

In 2022, on a whim, I applied to Creatives Rebuild New York's Guaranteed Income for Artists program, which supplied 2,400 artists in New York state with $1,000 a month for 18 months, with no strings attached. It was completely non-merit-based, a prize awarded to, according to CRNY, a random group pulled from the 22,640 applicants who met the qualifications of an "artist" in a variety of mediums, one of which was writing. The lottery was weighted to favor people who were "of color," LGBTQ, immigrants, caregivers, and other qualifiers of being underrepresented. I didn't even have to give up a job if I got one (I did). As a Black unpaid blogger, I made the cut, and began receiving $1,000 on the 15th of every month in September of 2022. It pretty much changed my life. I got my last payment in February.

The program, a one-time initiative that was funded mostly by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, was a $40 million-plus response to the increased precarity of artists, a situation highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

If I'm going to be honest, the early pandemic was one of the least financially precarious parts of my adult life, a reality that only highlighted just how much being rent-burdened—spending a sizable chunk of my income on housing—had dominated my life. In 2019, I had a steady job at NYU writing statistics papers about Obamacare, making a $48,000 salary. I was trying to do the "write on the side" thing, but I would often leave freelance drafts open on my second monitor, and I was taking such long walks that I had to be called into HR about it. After that job ended, I started working at GrowNYC, the company that runs most of the city's farmers' markets. Unemployment from leaving that job was paying me more than any job had ever done, with stimulus checks as a fun garnish. There was an eviction moratorium, so I was withholding my rent. Looking back through my eBay receipts from 2020 and 2021, I was spending it on gear for my pandemic hobby (fishing off the Coney Island pier), books by Ann Powers and Fran Lebowitz, a pair of nice headphones, and a Nintendo Switch. But it was clear from the beginning that all of this COVID cash was going to end some day, and it did.

In a press release announcing the guaranteed income for artists program, the president of the Mellon Foundation wrote that "it’s critical for the vibrancy of our cities that we recognize that making art is work, and artists are among our nation’s most dedicated and necessary drivers of our economy." But this money wasn't meant to encourage any particular artistic output—it was just meant to improve artists' lives.

It definitely did that for me. When those $1,000 checks began to arrive, I started to pay my rent again and focused on my craft: reading books and blogging critically. Above all, I went on walks, I hung out, and took in the city.

My life became my own little version of the stories we've all heard, about artists making their way in the city when paying rent was not the ordeal it is now—for the first time in my adult life, I didn't feel the need to hustle, I could just hang out and buy drinks with my freelance checks, and become a critic that flitted between openings and parties with a MetroCard. I had the time to get out all the good ideas I had that were actually bad ideas, and then started having actual good ideas, and my work improved.

There's been a protracted surrender on the idea that in New York City, being an artist can be your day job. That era ended, thanks to soaring rents and housing scarcity, and in its place is the era we live in now, ruled by the artist-hustler, the full-timer who squeezes out creative output until they're ushered into the six-figure of nirvana of, say, copywriting, or getting staffed in the writers' room of a studio movie. The other day, the online magazine Byline ran a profile of a buzzy young musician in a band called Rebounder. The hook? He's in a band, but he also has a job at GIPHY. The music is nothing special.

It can feel that pure creativity is increasingly marginal to the lives of some of the most prominent artists in the city. At times, that bleeds into and becomes the work itself. Becoming popular on social media seems like the only answer to how to go on: Bands are writing songs about feeling like products in the cultural marketplace, painters have become even more preoccupied with their place in the image economy, writers are now realizing they need to become influencers to survive, and so they write about clout, and singers sing about clout, and filmmakers are making films about clout. Not much seems to succeed. The vibe shift never came, the work has just gotten grayer and uglier.

Fresh off of having my rent paid for 18 months, I think I have the solution: Free money.

It's embarrassing (and time-consuming—have you ever filled out a typical grant application?) to ask for money. It's not glamorous to pick fights with the forces that are depressing New York's creative economy: rent, poverty, cartoonish income inequality. So we distract ourselves with whatever our pet peeves are. Case in point: the recent Baffler essay by the video artist Andrew Norman Wilson, his log of surviving the Trump era as a working artist. In telling the reader about the various contortions he's made to eke out a living dependent mostly on his work, Wilson largely places the blame for not being accepted into certain shows and the consequent financial hardships he's faced not on the financial inhospitality of our society to the working artists, but on the DEI-fication of the art world, which is run by "delusional incompetents with advanced deskilling degrees."

Wilson doesn't want to concede that these are two different complaints, perhaps because admitting you just want money is too humiliating, too debasing to his idea of his place in what he surely imagines is a meritocracy. He might resent the "multi-point oppression" system that the CRNY used in its selection process. But Wilson's precarity was probably not caused by the comparative success of a few non-white artists he resents. On the contrary, it's his proximity to those very artists, and to everyone else struggling to make life work in America.

I was recently reminded by a fellow writer how anomalous the notion of a "working artist" is, how it really defies the entire logic that our society, or any society that I'm aware of in the history of humanity, has operated on. Why should artists get to make money off of their personal passions, unlike everyone else? But, I argued, artists are the cornerstone of New York's brand and economy! It's certainly a cornerstone of New York's brand, the writer conceded. But a cornerstone of its economy? Had I seen the budget?

To an extent, I'm sympathetic to the notion that artists should pull themselves up by their bootstraps and log into the email mines with the rest of society. But so long as the mayor continues to insist on having Alicia Keys belt out that this is a "concrete jungle where dreams are made of" every time he enters a room, we should remember that she started her career in state-subsidized artist housing.