Mets owner Steve Cohen's quest to build something undisclosed atop the parking lots around Citi Field—psst it’s a casino—held its coming-out party on Saturday, as roughly 450 Queens residents and assorted Mets fans trooped through the stadium’s Piazza 31 Club to provide input on what they would like to see sprout in the team’s infamously barren surroundings.

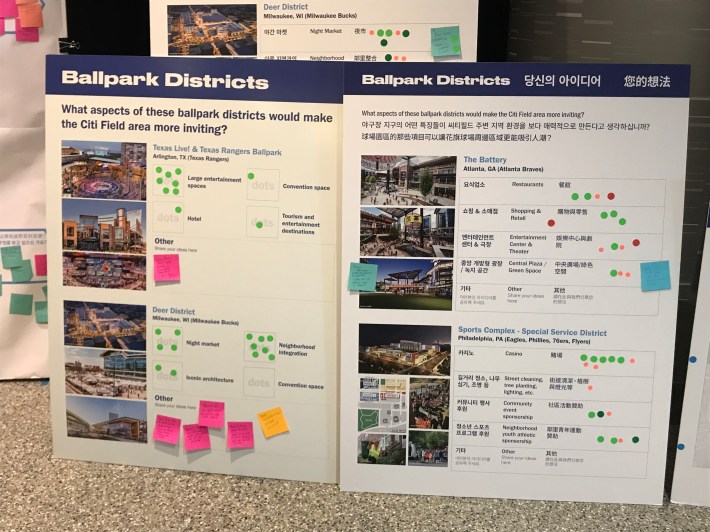

Professional moderators from planning consultants FHI Studio led visitors through a series of "visioning" stations where they could share their wish lists for transforming 50 acres of "vacant asphalt and wasted opportunity" into something that could just possibly knit the stadium into the adjacent neighborhoods of Corona, East Elmhurst, and Flushing.

"I have no problem with it, if it models what they did at Aqueduct," said Cindy Custodio, a lifelong Mets fan from Fresh Meadows, of a possible casino. "If you’re telling me this is going to become part of a community with restaurants, gaming, a district for everyone to come to for entertainment, shopping."

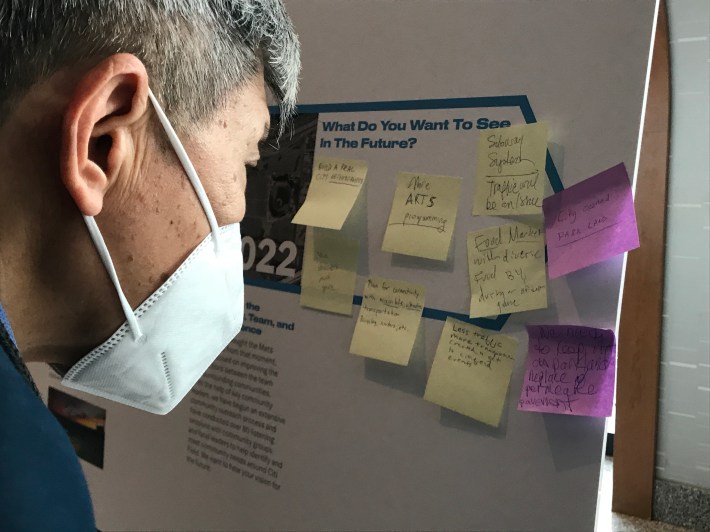

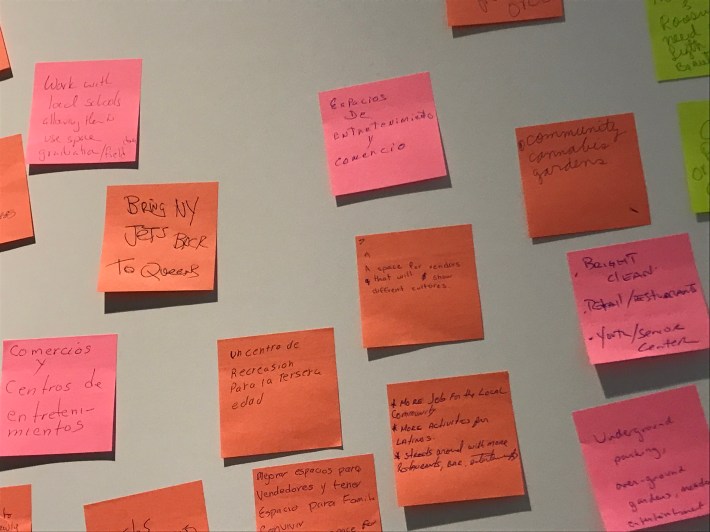

That’s doubtless how Cohen hoped coverage of this event would go. But as much as there was plenty of actual visioning on hand—numerous poster boards were left festooned with Post-its reading "Build a real city neighborhood" and "public art by local artists"—it’s an equally valid reading, as several participants noted, to see it as the opening gambit to allowing baseball’s richest owner to cash in on public land that Mets ownership has long salivated over, but never quite been able to obtain.

Some backstory here: When the state authorized the construction of Shea Stadium, Citi Field’s predecessor, as part of Robert Moses’s last gasp, it was on land that had never been much more than an afterthought. Originally marshland along Flushing Bay, later to be the coal heaps featured in "The Great Gatsby" as the Valley of Ashes, the future stadium site was purchased by the City in the 1930s but never incorporated into Flushing Meadows-Corona Park to the south. Instead, it took shape as a classic 1960s stadium-in-a-sea-of-parking, even as on the City’s books it remained public parkland, albeit parkland where the only greenery was the stadium’s outfield grass.

This parkland designation became an issue when, in 2012, then-Mets owner Fred Wilpon and his son Jeff announced that they were partnering with Related Companies, the developer of Hudson Yards, to build a massive shopping mall, dubbed Willets West, in the Citi Field parking lot. Five years and several lawsuits later, Willets West had a fork stuck in it by an appeals court judge who ruled in no uncertain terms that parkland can’t be used for anything other than recreational purposes unless the state legislature specifically acts to allow it.

When Cohen took possession of the Mets in 2020, at a cost of $2.4 billion of his estimated $14.6 billion in net worth, he made no mention of wanting to revive Willets West or do anything else with the stadium lots. But that was before Governor Kathy Hochul announced she was opening up applications for three additional casino licenses, to be specifically reserved for sites in and around New York City.

According to the request for applications issued last week by the state’s Gaming Facility Location Board, the rubric for choosing winners in what’s expected to be a years-long selection process includes the "integrity, honesty, good character and reputation of the Applicant," "the business ability of the Applicant to establish and maintain a successful Gaming Facility," and a solid plan for job creation. Cohen, who is expected to partner with casino operators Hard Rock for his proposal, should be able to vouch for all of that, so long as the state doesn’t look too hard at his hedge fund’s past dalliance in insider trading that resulted in a $1.8 billion fine.

Before any bills can be stuffed into slot machines, though, Cohen’s plan will need to pass muster first with the state facility location board; then with a neighborhood community advisory committee consisting of representatives appointed by the mayor, governor, city councilmember, state assemblymember, and state senator; then with the city council for any needed zoning changes; and then back to the state board for a final decision.

Saturday’s visioning festivities, if not part of the formal approval process, kicked off the battle for hearts and minds that help guide those ultimate decisions. (Cohen press officer Karl Rickett noted that three invite-only sessions had been held previously for residents of surrounding neighborhoods, and about a dozen more are planned for the coming weeks and months.)

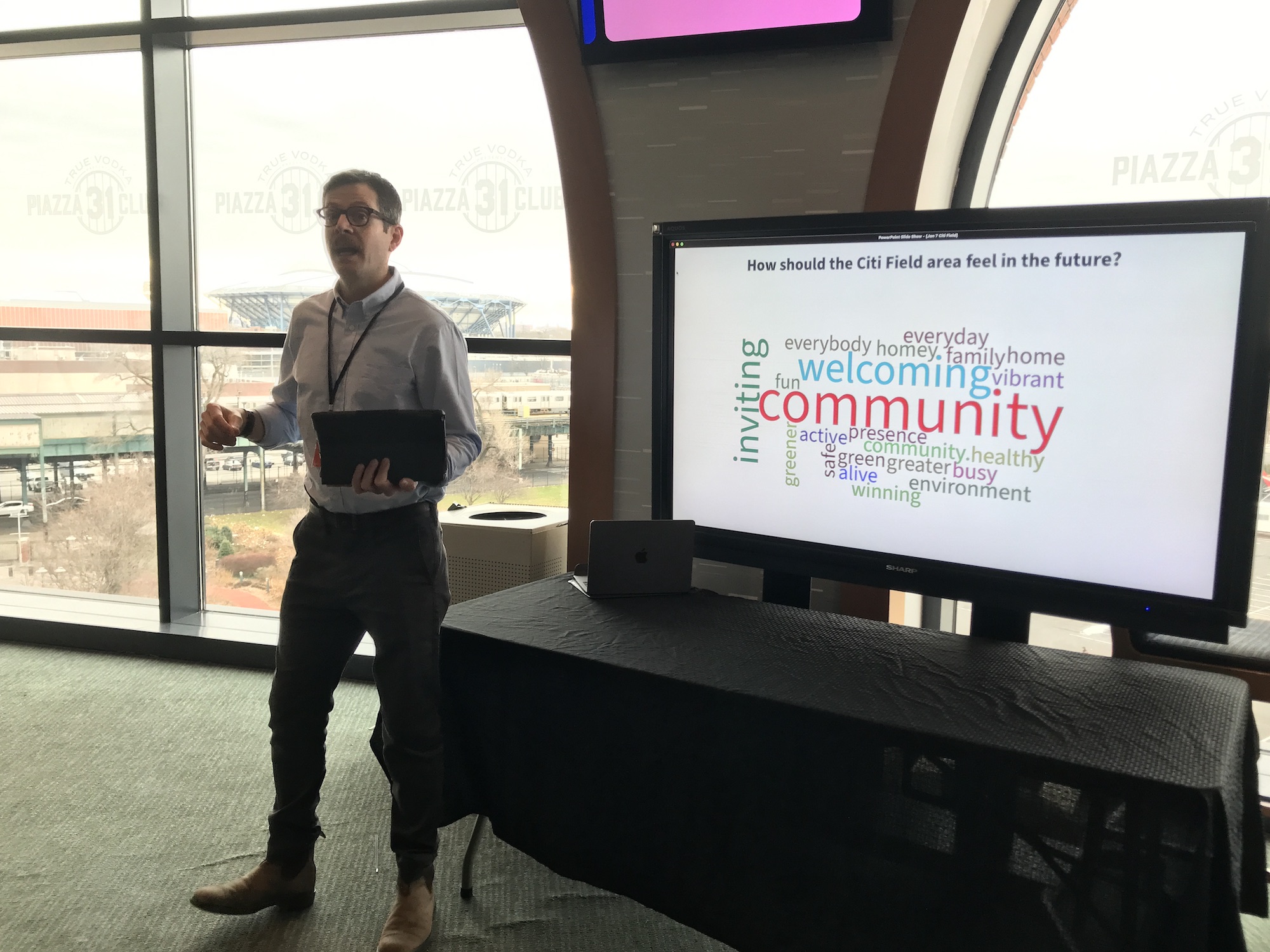

The presentation included very little information about Cohen’s actual plans—the man himself put in a cameo but stuck to generalities—preferring to stick to open-ended questions about what local residents would like to see built; handwritten suggestions from the masses included a “jobs training center,” “soapbox derby track,” and “community cannabis gardens.” (There were a lot of Post-its, but a quick scan of those on display revealed no one actively requesting a casino.) These were accompanied by some more subtly coercive elements, such as video screens asking what people think of the Citi Field environs today and what they would like to see in the future, displaying sample word clouds highlighting "barren" and "empty" for the before scenario and "welcoming" and "community" for a Cohen-redeveloped future.

"It’s kind of a push poll, in that it’s presupposing that you want something done," said one Mets fan from Great Neck who gave his name only as Tom. "There’s a smorgasbord of possibilities, and they’re all nice, and they all sound interesting. But you don’t see the word 'casino' anywhere, and everybody knows that’s what this is about."

"I feel like this is the first step in a developer’s progress to say that they had community input," said Sunnyside resident Amparo Abel-Bey. Her partner, Philip Leff, added, "We’ve both seen this play out more than a few times." Both, though, expressed optimism, or at least hope, that Cohen would actually take some of the public’s suggestions to heart—in their case, requests for more bike parking, more public restrooms, and a "ballpark district" that involves local businesses. "There’s an opportunity, and we’re going to have to take advantage of that," said Abel-Bey.

Mixed feelings were definitely the order of the day. Even as Custodio expressed hopes for more shopping and other amenities like restaurants, she worried that a new destination development surrounding Citi Field could create new traffic headaches, something that she said the neighborhood can’t afford, especially with New York City FC and Mayor Adams targeting a site across the street in Willets Point for a new 25,000-seat soccer stadium.

"I walked around maybe 20 minutes, and the word I heard singularly was 'congested,'" said Custodio, as her twin children munched post-visioning hot dogs. "That’s a problem. If your entire neighborhood is telling you that it’s congested, we’re telling it to you because it’s our everyday life: Try to avoid this place at all costs."

Tom echoed her traffic concerns, especially if a casino and soccer stadium were to be added to an area that already becomes a sea of cars every fall when the U.S. Open coincides with Mets games. "If you build a multistory parking garage to take the place of this immense parking lot, in addition to the immense parking that you’d need for a casino, and everything else that might be thrown into the mix, it might take hours to get out of the parking lot after a game," he said.

Andre Maloy, wearing a Mets earring and a sweatshirt bearing the name of the East Elmhurst-Corona Civic Association (he’s on its board, as well as Queens Community Board 3), said, "What I would like in this area is something that would draw the community together." He is "all for a casino," he insisted, but also concerned about traffic: At the Empire City Casino in Yonkers, he noted, "It’s one way in and one way out, and you can sit there for 45 minutes trying to get out, and when they close it at 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning, there’s horns blowing — and you come out and you’re right in the community." How would he like to see development mitigated to avoid traffic nightmares? "I have no idea how they could make it work. But I would like to see them figure it out."

Even if the monumental traffic concerns are somehow addressed, Cohen still has nowhere to build a casino other than the stadium parking lots—which, as noted, have been repeatedly declared by courts to be off-limits to permanent development. This would leave the Mets honcho with only two options: Throw enough high-priced lawyers at the inevitable lawsuits to convince state judges that a casino (with, possibly, a park around or on top of it?) is more recreational than a mall, or throw enough high-priced lobbyists at Albany to convince the state legislature to demap the parkland (a process termed “alienation” in state law) and turn it over to him for development.

There’s also the question, evaded by all of the presentation materials, of who would pay for it: Even if Cohen and his business partners funded a casino itself (starting price: a $500 million licensing fee to the state) and any other parks and shopping and bike racks he might throw in to sway public opinion, there’s the question of whether he would be able to evade paying rent and property taxes on the massive City-owned site. (Land deals of this sort are becoming the flavor of the month in pro sports: Angels owner Arte Moreno spent years working out a sweetheart deal to get development rights to his team’s ’60s-era parking lots, only to see it all fall apart when the mayor he’d cut the deal with turned out to be under FBI investigation for allegedly soliciting bribes in exchange for the stadium’s approval.)

Nothing is likely to happen anytime soon: The casino approval process could take years, and a court resolution could take even longer, assuming the state legislature doesn’t preempt lawsuits via alienation. (The last time a New York sports team owner wanted to build on public parkland, then-Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver quietly dropped a bill alienating Bronx parks for the Yankees onto legislators’ desks the final day of the 2005 session, and most of them voted for it without ever bothering to read it.) Saturday’s dog-and-Post-it show, then, was likely the first step in a long campaign to rebrand a developer’s cash grab as giving the people what they want. And if one 60-something Connecticut resident may have written down "casinos," then why not that, too?