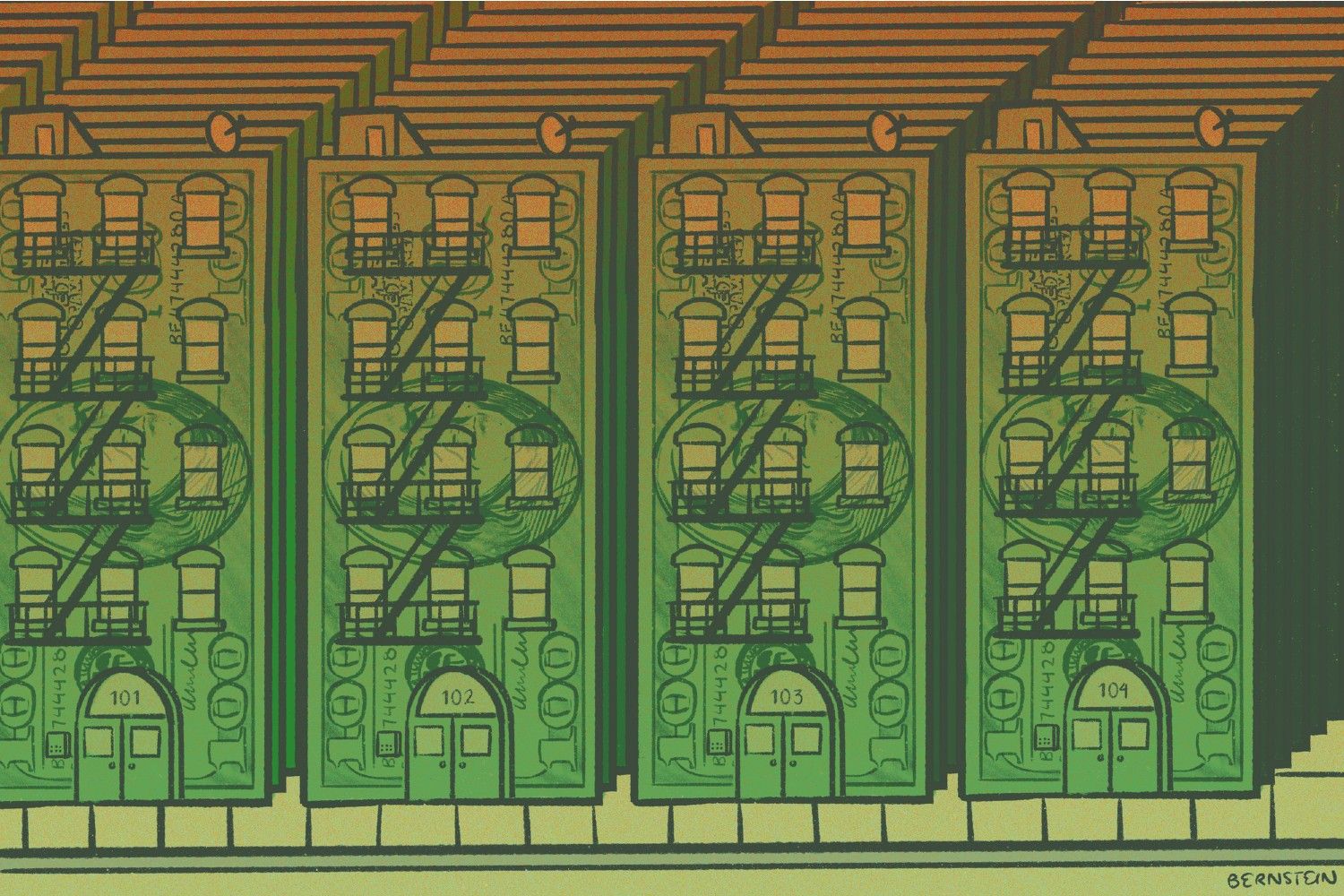

Want a Rent-Regulated Apartment? Pay This Broker $10,000

Brokers are capitalizing on an already exploitative rental market, and in the process are effectively destroying the few rent protections we have.

10:30 AM EDT on June 9, 2022

Emily Bernstein / Hell Gate

This spring, Rina Davidson found herself in the excruciating position of trying to change apartments. Like a lot of people who move in New York City, where rents have recently risen 33 percent, Davidson was propelled not so much by a desire to level up as a need to escape an untenable situation. Her ceiling had been leaking for six months; the landlord appeared not to care.

One listing on StreetEasy looked appealing enough—a walk-up apartment in a townhouse on East 89th with a "faux fireplace that sets the tone for the space," according to a blurb. The two bedroom was listed for $3,150/month. Davidson, a medical student, tossed off an inquiry to Sarah Pemberton, the broker who'd intermittently listed the space since late 2020.

Davidson received an odd response: The "unique listing," wrote the broker, was rent stabilized and the "actual rent" came out to $2,250: "Therefore the fee is 10k. If you do the math it’s a big savings first year and a huge savings every year after that."

The bizarre practice of charging tenants a "broker fee" for the privilege to spend well over a third of their income on housing has long vexed New York City renters. Until recently, brokers tended to charge the equivalent of one month's rent. In some cases, their fees might top out at 15 percent of an apartment's annual cost.

But the $10,000 fee Davidson was quoted was nearly 40 percent of what she'd expect to pay for the rent-stabilized unit every year—and more than double a typical 15 percent broker fee.

"It was wild," Davidson told me. "I obviously didn’t move forward." And besides, it turned out the apartment was a railroad, which she and her roommate felt was less than ideal. In the end, they renewed the lease on their leaky unit because unlike many landlords, theirs chose not to raise the rent this year.

We emailed and called Pemberton and her agency, City Wide Apartments, asking for clarification on this $10,000 fee. Was it a finder's fee for a particularly desirable apartment? Was it paid out monthly, or in a lump sum? If the rent was now stabilized at $2,250, why had the agency listed it for $2,900 last year, and $2,704 the year before? Those requests went unreturned.

Johannes Wetzel, a real estate attorney, told me he's seen an increase in exorbitant charges of this sort, particularly among rent-regulated units. "It just stinks," he said. "Why would an arrangement like that exist?"

New York is among the few cities where tenants, rather than landlords, pay brokers for the services they provide. It's a practice that's difficult to justify even when it comes to unregulated, market-rate units—and one that's particularly obscene when it costs tens of thousands of dollars to secure the ability to pay "affordable" rent in a regulated apartment. As the entire citywide real estate apparatus scrambles to capture the profits generated by the tightest housing market in recent memory, extreme pay-to-play schemes for affordable housing units are apparently becoming more commonplace.

"This practice of extortion via broker fee is an enormous barrier," said Cea Weaver, a campaign coordinator for Housing Justice for All. "Even if you have rental assistance to cover the cost of rent, the broker fee alone will make using that subsidy and finding stable housing impossible."

Charging a broker fee on a rent-regulated apartment may violate the spirit of affordable housing laws, but it's perfectly legal, a convenient loophole through which brokers can generate significant cash.

New York's Department of State oversees housing law and licenses real estate agents, regulates security deposits and application fees, and handles reports of "key money," the illegal fees some landlords ask for in exchange for a lease. But brokers can charge as much as they want: The customary cap of 15 percent of annual rent is essentially based on what brokers think tenants will pay.

The DOS tells me there is "no one statute or regulation that determines what is an appropriate fee," though as the agency notes, "a fee must represent charges for actual services," which is a debatable metric if the services rendered are answering StreetEasy emails and performing a third-party background check.

"When I moved in 2019, one month was standard," a 26-year-old named Andrew Dakan who recently relocated to the East Village told me. "Now they’re all at least 15 percent," which, given the current median rent in the city, comes out to over $5,000, plus a security deposit and at least one month's rent. Dakan took out a loan to cover the $9,000 it cost to leave his apartment in Hell's Kitchen and move across the island, two miles away.

The crush he's feeling from some of the city's most maligned professionals appears widespread. Following a slate of housing reforms a few years ago and a legal challenge from a consortium of lobbying groups, broker commissions are among the only completely unregulated fees associated with renting an apartment in New York.

"Look, this is just my opinion," Dakan said, "but I don't think brokers should exist."

The ubiquity of broker fees is one of the many New York City mysteries best explained by the fact that people like to make money, and once an industry is accustomed to harnessing an avalanche of cash, it can be quite difficult to stop. In 2021, the New York Times referred to the practice as "archaic," a holdover from the pre-internet age in which a broker might actually have a real job, like digging through apartment listings themselves.

A few years ago, when Gothamist posed the question of why New York tenants pay steep broker fees, it found that the state's most powerful real estate trade organization, the Real Estate Board of New York, had once been critical of the practice. In 1945, after a tenant was reportedly charged a broker fee of one month's rent, a REBNY representative told the Times that the fee represented "an exploitation of the housing shortage." In an email this week, however, the organization wrote that "there are thousands of hardworking real estate agents across New York State that deserve compensation for their work," and referred us to city and state guidelines around "appropriate charges and fees."

There's no law that requires rent-regulated apartments to be rented to low- or middle-income New Yorkers, so "high broker fees have the potential to really magnify the impact of that program design choice, keeping households most in need out of rent-regulated units," said Charles McNally, a representative for the Furman Center for Real Estate and Housing Policy.

But, McNally said, prospective tenants who are able to cough up a couple grand on demand are also probably attractive to landlords, as broker fees act as a functional "screening mechanism" indicating significant access to wealth.

One broker, Stephen Berthomieux, told me he doesn’t feel good taking tenants' money for broker fees, though if a big company like Google is paying a client's relocation costs, he'll definitely accept that cash. But most of his clients are moving because their landlords are raising rents to "insane" and "brain-melting" levels, sometimes more than a thousand dollars a month.

Berthomieux said when demand for an apartment is so high, and the availability of units is so low, "no management company in their right mind is going to pay me to bring in a tenant to rent an apartment." But the 50,000-odd brokers working in the state still need to get paid, which is how all these costs traditionally get passed down to the person who will be also signing away a portion of their income for the next 12 months.

The state briefly, if unsuccessfully, attempted to address broker fees with 2019's Housing Stability and Protection Act, a 74-page piece of legislation that affected nearly every stage of the rental process, from application fees to security deposits. It also, notably, made it nearly impossible for a landlord to deregulate a rent-regulated apartment, a process through which an owner could remove rent protections in instances where a tenant's income or a unit's rent rose past a certain point.

Though the legislature hadn't expressly addressed real estate commissions in HSPA, in February 2020, the Department of State issued a stunning piece of further guidance requiring landlords, rather than tenants, to pay broker fees. It lasted about a week, a week during which lawyers for REBNY prepared a challenge in court. Their argument hinged on the rather obvious fact that real estate commissions hadn't been mentioned in the act, and further pointed out that the people whose livelihoods depended on collecting tenants' money hadn’t been involved in the change. Following a chaotic period of $800 application fees and overnight rent increases, a judge suspended the ruling while it made its way through the courts. In May of 2021, the brokers finally won.

In the year since, as rents soared, the industry rolled along unchecked. This May, a studio went up for rent in 26 West, a massive luxury building on Greenpoint's waterfront built by the Rabsky Group in 2016. The building has a yoga room and a part-time doorman; as a recipient of the controversial and lucrative 421-a tax break that was until recently handed out to developers, it's also required to offer a certain number of "affordable" units subject to rent regulation. Billy Taylor, a tenant organizer, recently emailed about the open unit and was told by the broker that the apartment was "rent stabilized" at $2,598. That said, there would be a 35 percent fee due at lease signing, which amounted to $11,331.

Taylor said he has contacted a few elected officials in the weeks since, convinced this is a way to functionally raise rents. "It's an incestuous relationship between an exclusive broker and a management company," he said.

The broker didn't return requests for an interview, but the building's owners vehemently dispute there's collusion of the kind that Taylor described happening here. A representative for 26 West, Hersh Rosenberg, told me "the owners of the building were very surprised that the broker was taking advantage of the tenants" and that they had communicated to their brokers not to take fees "exceeding the standard in the market of one to two months" of rent. A tenant who had originally agreed to pay the 35 percent fee, Rosenberg said, had that sum downgraded when they recently signed a lease.

Wetzel, the real estate lawyer, said he is seeing more rent-regulated apartments where the broker fee "is very, very high." He expects the practice to become more common, but he can't figure out what incentive a landlord could possibly have to let their representative try to collect such an unreasonable amount. Perhaps it's just that agents get lucky with these sought-after units and, unless the laws change, can charge whatever they desire. But he also wonders if the 2019 laws might have had an indirect impact on this corner of the market, since they made it tougher for landlords to profit from rent-regulated units. "I think landlords are trying to figure out a way to extract the actual market value of these apartments," he said.

Julia Salazar, the state senator from Brooklyn who introduced a bill to ban these kinds of broker fees last year and was a vocal proponent of the 2019 housing reforms, told me that remedying the situation will require meaningful legislation.

"Broker fees are reportedly skyrocketing, which needs to be regulated," she said.

This is New York real estate: If there’s a loophole through which extra cash can be made, someone will definitely get paid. "If there's value to be extracted from these apartments," Wetzel said, "the landlords and the brokers are going to try."

Thanks for reading!

Give us your email address to keep reading two more articles for free

See all subscription optionsStay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Hell Gate

This NY Times Columnist Should Probably Not Be Teaching John Cage to Columbia Students

John McWhorter can't be serious. He just can't be.

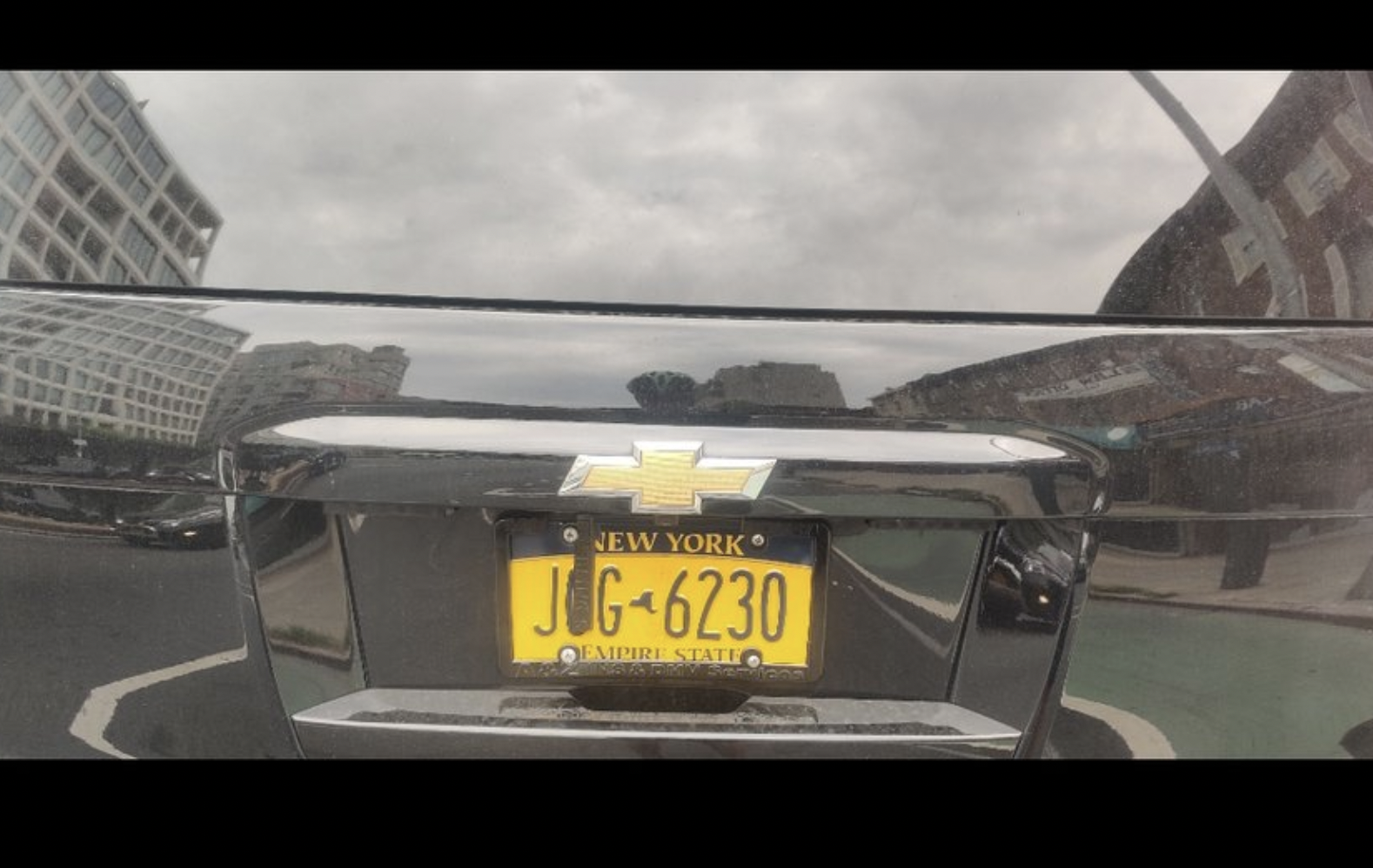

One Weird Trick for Getting Away With Obscuring Your License Plate

New York state lawmakers increased penalties for toll scofflaws, but also explicitly gave cops the power to cut them loose.

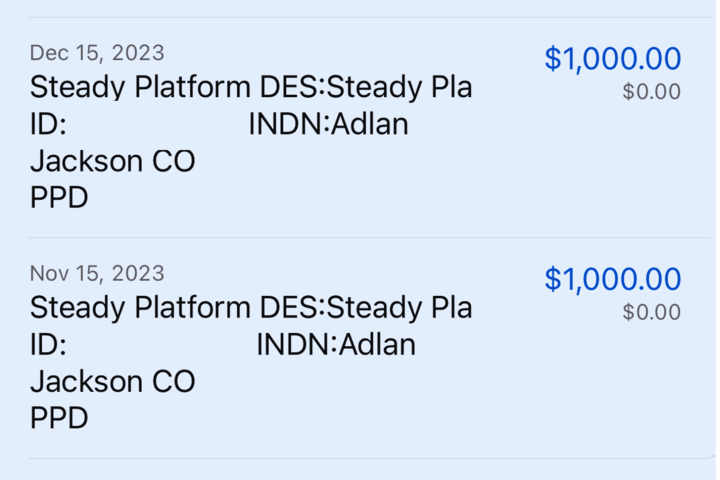

This Pandemic Program Gave $1,000/Month to Artists to Stay in New York. It Worked for Me

One way to support the arts in New York? Pay people’s rent.

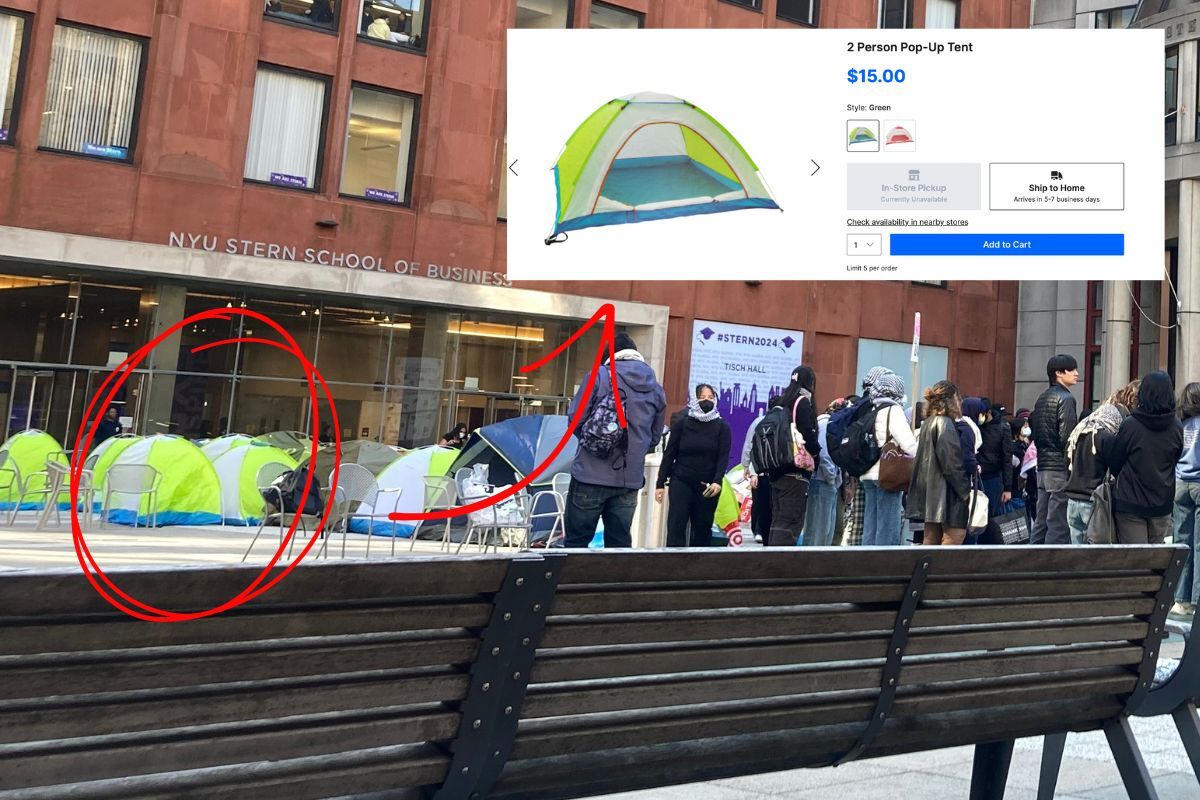

Mayor Adams Suggests ‘Outside Agitators’ Created Tent Conspiracy to Ruin NYC

This goes all the way to the Big Top, and more news for your Wednesday morning.

Report: Mayor Adams Was Not, Strictly Speaking, ‘Ready’ For 8 Inches of Rain in September

And more links to clear out of your catch basin.