A Star-Studded Climate-Crisis Movie That’s Actually Good

In Earth II, mash-up pranksters the Anti-Banality Union take on ecological devastation, civil unrest, and Elon Musk

7:45 PM EDT on May 24, 2022

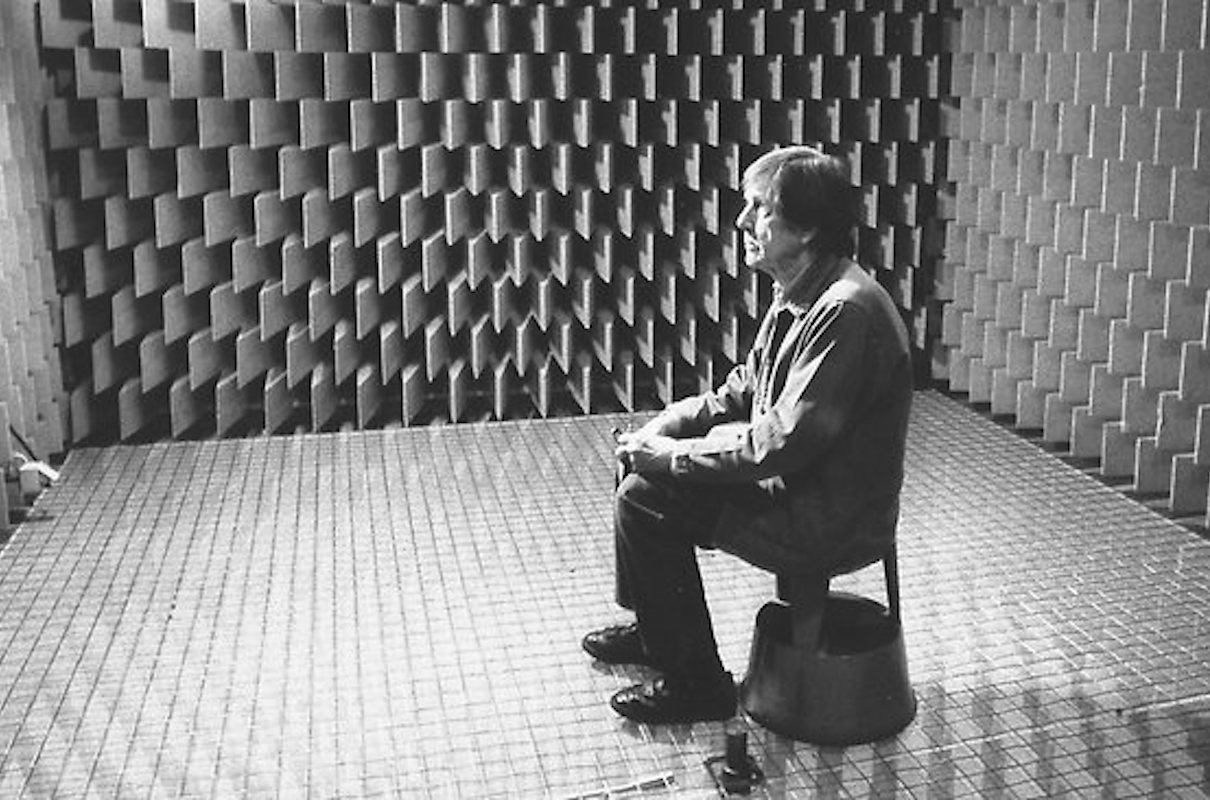

The latest Anti-Banality Union film reconstextualizes Hollywood movies to tell a new story about climate crisis and martian mania. (Anti-Banality Union’s “Earth II”)

For more than a decade, an anonymous collective of NYC filmmakers known as the Anti-Banality Union has been churning out deeply peculiar, disturbing, hilarious feature-length films composed entirely of the chopped-up, Frankensteined pieces of mainstream popular movies. Their debut outing, "Unclear Holocaust," was a subversive retelling of the events of 9/11 through the lens of Hollywood's ongoing fantasy of the destruction of New York City. "Police Mortality" contemplated the violence of policing turning inward on itself. "State of Emergence" conjured the panic of zombie movies with the zombies subtracted.

Now, the Anti-Banality Union is out with its most ambitious film to date, "Earth II," which tells a familiar story of spiraling climate disaster, a widening gyre of social upheaval, and the ambitions of the ultra-wealthy to neatly escape it all by leaving the planet. It is screening at the Anthology Film Archives June 3 and at UnionDocs June 23.

Hell Gate spoke with the three filmmakers behind the anonymous collective about their latest outing.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Nick Pinto: It’s been a while since your last movie. What have you been up to?

The Anti-Banality Union: There were ideas of this film back in early 2016. We started working on it really in earnest in early 2017. But this took much longer than our previous films because it was a far more involved process. Formally, we decided to try to make the film as cohesive as possible and to make it really more of a narrative film that one could really follow in the same way that one watches a typical Hollywood film, which involves way more labor. A lot of thought went into it. We storyboarded this one a lot more carefully. In our previous films, the narrative form was dictated more by the source material.

Originally, it was supposed to be the history of the human race. But we got into this idea that humanity's view of itself and its culmination is leaving Earth and colonizing Mars. So we decided to make a film that was just about climate disaster and the wealthy colonizing Mars. The moment we're in now! It seemed more far off when we started doing it. We preempted the billionaire space race by a number of years. We willed it into existence, in a sense.

That happened in a few ways. In the film, we thought of this idea of nuking a hurricane to stop it from hitting the US and making landfall. Maybe two years after we put that in, that Donald Trump proposed the exact same thing! So he must have seen a leaked copy of the film or something.

What happens in this movie?

The clearest way to sketch it out is by reference to the three protagonists. Will Smith, Matt Damon and Keanu Reeves, who all represent different subjective positions in this contemporary climate collapse moment. Matt Damon represents the desperate desire to cling to everyday life and routine. He represents a sort of middle-class aspirational tendency to mythologize the self-made billionaire. He's a fan of Elon Musk and is putting all his eggs in the basket of Mars colonization and wants to be a part of it.

Will Smith represents this right-wing, vigilante, Blue Lives Matter reaction to social disorder. And Keanu Reeves represents this messianic force that comes in and aligns humans with non-human life on Earth as an interspecies ally to lead the resistance against the forces of extractive industry and primitive accumulation. Those three characters represent those three forces and then what we see is what happens when those three forces butt heads.

Your previous films are very explicitly drawing on particular Hollywood genres. This feels a little different. Were you trying something new here?

In our previous movies their form was really determined by a single genre in each case. And in this case, it was more cross-genre and there are fewer moments that feel like supercuts of us cataloging genre tropes. And part of that also comes from the fact that we really took Syd Field's three-act structure as an earnest starting point for trying to craft as pleasurable a viewing experience as we possibly could. We really set out to write this film. We didn't really write a single word, but we tried to assemble a script of some kind that one could follow.

The beautiful thing about Hollywood movies is that essentially, anything we wanted to happen, we would find it eventually. It's there. Because if we can imagine it, it's only because we've already seen it in a movie. We knew that Matt Damon wanted to go to Mars, and then in a subliminal moment, we remember that there's a point where he begs for a ticket to go to Elysium. And we were like, "Oh yeah! That could be him begging for a ticket to go to Mars."

Is Hollywood just a vast reservoir of neutral cultural material for you, or does it have an agenda that you're trying to subvert?

We don't really ascribe agency to Hollywood itself as an entity as much as we used to. You can ascribe politics to our film, but everything that's said in the film is in these movies. We're just putting them in a specific order. The films we're drawing on are made by people. They're working within this Hollywood system where they have to maximize profit, but they make attempts to make some social statements or political statements. In Independence Day, critique of the aliens that go from planet to planet, using them up and extracting the resources and moving on to the next. Elements like that are buried in the material, but then if you compile them all together, you can see them.

One thing that tends to obscure these elements is that the movies, in their original form, tend to end with social order and family values being restored. That's why most of them end up being so unsatisfying. We're trying to remove that obstacle. We always say, "Don't watch the last 20 minutes of the film. And root for the bad guy."

Does "Earth II" have a happy ending, would you say?

We toyed with the idea of having a clear-cut happy ending, which didn't seem realistic or even possible, given the footage we had, but also we wanted to leave the door open to a possible future without being too didactic about what that might be. Obviously, climate change is a total disaster for the entire planet. But life is very resilient. And even if humanity nuked the entire planet, something would survive, and life would not be wiped from the universe. I don't know if that's a hopeful take, but we wanted to have a less anthropocentric vision of life in the film, and that's where the ending comes from.

How do you see this film in dialogue with the existing climate-fiction film canon?

There's not a lot. There's one strand we wanted to critique, that you hear from people who don't want to give up industrial capitalism, who say we don't actually have to stop our emissions, we don't have to slow down GDP, we can just come up with some technical solutions. We'll extract the carbon from the atmosphere, lower the global temperature, and it'll be fine. It's not fine! We wanted to question the idea that we can just find the scientific solution to this problem that doesn't actually require us to change anything, that either we'll fix it through science or we can leave the planet. It's so absurd! Even at its worst, this planet is going to be more inhabitable than Mars. We have air and water here!

A lot of cli-fi—[climate fiction]—works have climate scientists emerging as the heroes and the moral voice after world governments have failed to heed their advice. You get the sense that somebody has a very inflated sense of the power of climate scientists. In our movie, we try to decenter them so that they end up being supporting characters in a much more inscrutable play of power relations. There's kind of a cynical aspect in our movie as well, because our scientist, played by Aaron Eckhart, warns the government but then ends up becoming the leading scientist doing fundraisers for the project to leave earth.

There's also a sort of Deep Green Resistance faction depicted in this movie. Is there a critique there, or are you rooting for them?

There's definitely a critique. It's probably obvious that we have a certain fondness for that group in the film. There are some comedic elements to the way they're depicted. When one is involved in certain political struggles, especially around the climate, there is a sort of sense of heroism, a sort of role-playing that people fall into. That is something that we wanted to critique in the film. We wanted to present them using a variety of tactics, and sometimes that did not work. It was important to us that they failed, because we didn't want to buy completely into this fantasy version of what political action looks like. So there's definitely a bit of critique, but with a sort of open heart, so to speak.

Do you have a favorite part of the film?

Yes! Right before Matt Damon gets sent to Mars, he has a moment where he enjoys his last moments on Earth. And he watches an episode of “Planet Earth II,” with David Attenborough narrating, and he tears up watching it, as most do when watching Planet Earth. It's a really bittersweet moment, and you can really feel his pain. It's the most sincere moment in the movie.

This is the first of your movies where you're cutting in news footage alongside the Hollywood material.

We had a soft rule that we gave ourselves where we could use footage of news if it was depicted as news in the film. This film—more than the others—really felt like it was about the moment we were living through, so we just felt the need to have some context in that way. At the beginning of the film, we have a lot of news. We have Elon Musk; we have climate change; and we have general civil unrest. We were editing the film throughout the George Floyd uprising. So there was no question contemporary news was going to be depicted in the film. And given how frequently Wolf Blitzer is cast actually delivering scripted news in these movies, it didn't really feel like cheating at all.

Do you have a count of how many films you actually cut up to make "Earth II?"

We did, but we lost count. So, literally countless?

Your previous movies are available on the internet, but you're focusing on live screenings this time. Why?

Part of it is the experience of the last few years of being remote all the time. Part of it is the realization that the internet's maybe not a liberatory space. So we want to emphasize showing it in person to actually encourage people to make some real physical connections with each other.

We're hoping this can be an occasion for people to come together and meet each other, find each other, collude with one another.

Thanks for reading!

Give us your email address to keep reading two more articles for free

See all subscription optionsNick Pinto served two tours as staff writer at the Village Voice. His reporting has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Gothamist, The New Republic, Rolling Stone, The Intercept, and elsewhere.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Hell Gate

Two West Village Newcomers Bring Fresh, Delicious Energy to the City’s Increasingly Predictable Burger Game

Burgerhead and Smacking Burger (located in a gas station) surprise and delight with their simple pleasures.

Eric Adams Still Wants to Cut Library Funding—But Don’t Worry, We’re Getting 1,200 More Cops

And more news for your Thursday.

This NY Times Columnist Should Probably Not Be Teaching John Cage to Columbia Students

John McWhorter can't be serious. He just can't be.

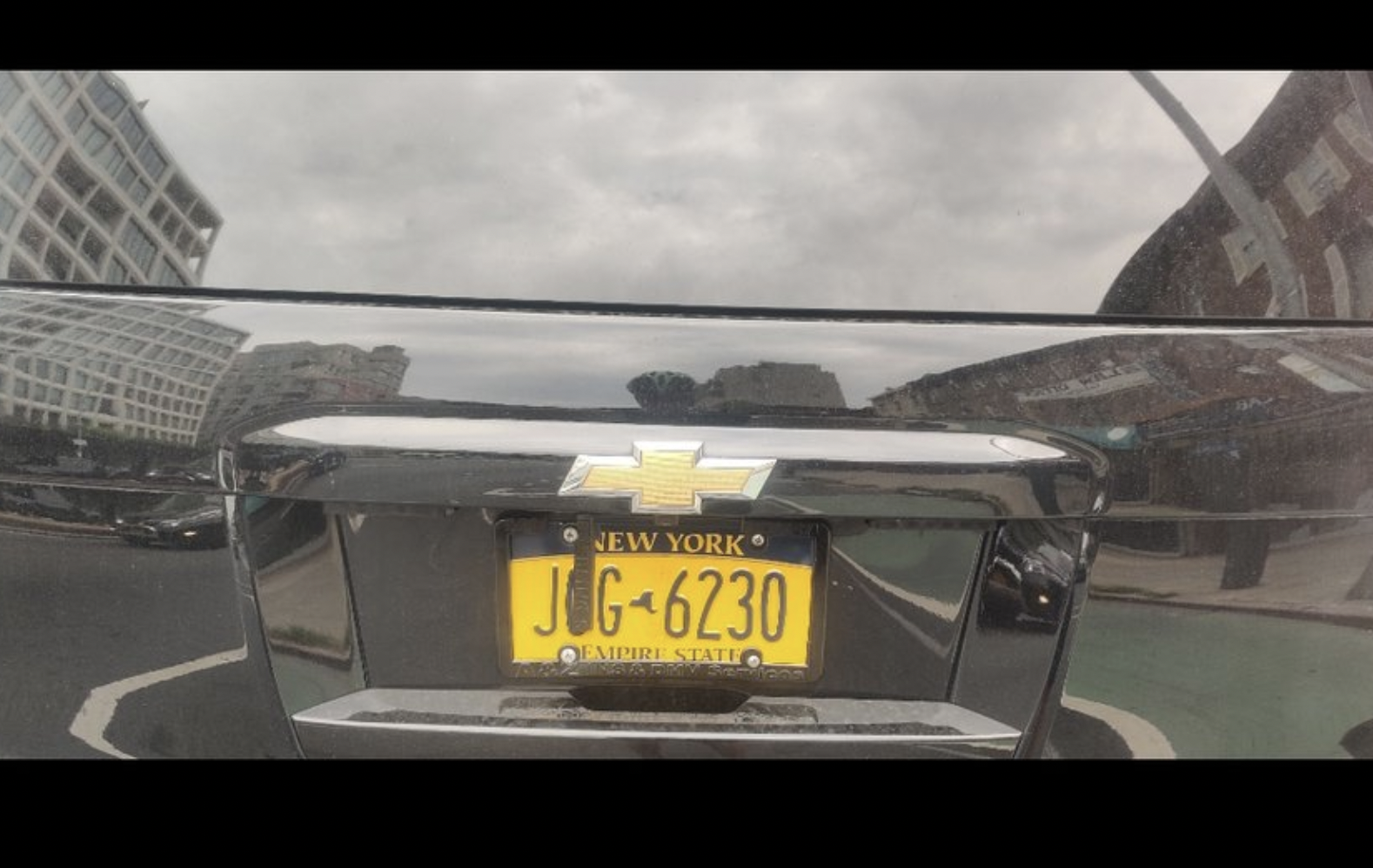

One Weird Trick for Getting Away With Obscuring Your License Plate

New York state lawmakers increased penalties for toll scofflaws, but also explicitly gave cops the power to cut them loose.

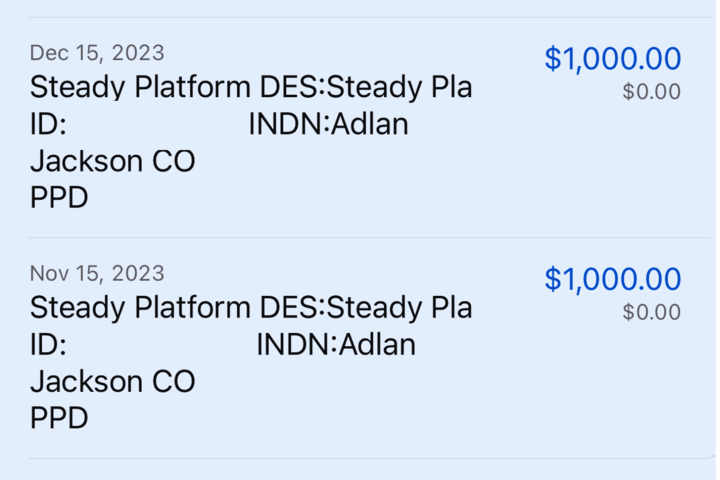

This Pandemic Program Gave $1,000/Month to Artists to Stay in New York. It Worked for Me

One way to support the arts in New York? Pay people’s rent.